OF THE PASSION:

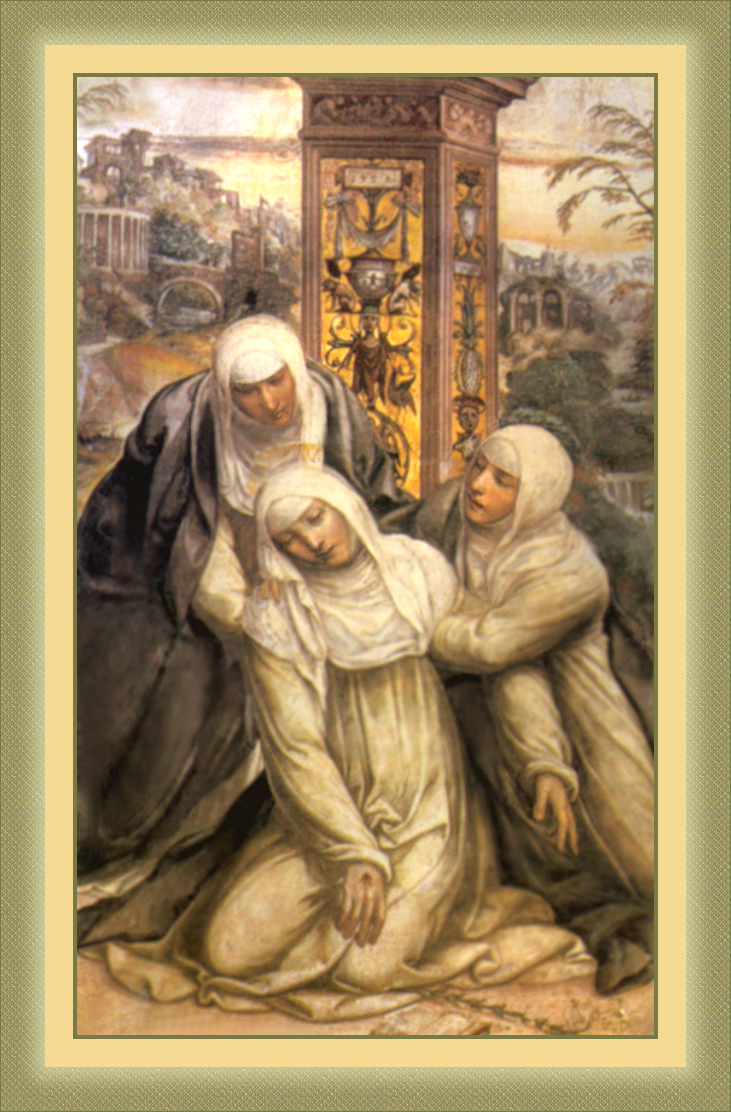

+++++++ Saint Catherine of Siena +++++++

| St.

Catherine of Siena: Biography Adapted by Catholic Tradition from SAINT CATHERINE OF SIENA by Mother Frances A. Forbes, a nun of the Society of the Scared Heart in Scotland who was a convert and highly regarded by Cardinal Merry de Val, a close friend of Pope St. Pius X. Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur, 1913. Currently published by TAN BOOKS. Chapter 8 THE SEED OF SORROW  N the death of Gregory XI, the

Cardinals were resolved to elect a Frenchman as Pope. N the death of Gregory XI, the

Cardinals were resolved to elect a Frenchman as Pope.The papal court would then return to Avignon and take up the old easy life with its luxurious surroundings. The Romans, on the other hand, were determined that Gregory's successor should be an Italian, and they lost no time in letting their intentions be known. During the conclave that was to decide the question, a huge crowd gathered round the Vatican shouting, "Give us a Roman or at least an Italian Pope!" An embassy consisting of the most eminent men in the city waited upon the Cardinals to warn them of the popular feeling. During the night there were riots in the streets and the state of affairs looked somewhat threatening. The French Cardinals, who could not agree as to their candidate, thought it better under the circumstances to elect an Italian. Their choice fell upon the Archbishop of Bari, a Neapolitan, a man whose honesty and purity of life caused him to be universally respected. The election took place amid a great turmoil, but there is no doubt that the Cardinals themselves considered it valid. On Easter Day the new Pope, who had taken the name of Urban VI, was crowned, and the Sacred College, having made known the result of the conclave to the sovereigns of Europe and to the six French Cardinals who had remained at Avignon, made their act of homage to the new Pontiff. Urban was known to all as a man of austere life, zealous for the glory of God and the good of the Church. Those who knew him well were aware that he had a harsh and severe temper, but they were scarcely prepared for what was to follow. The new Pope set about the difficult work of reform with a violence and a want of tact that destroyed all the good he was earnestly trying to do. He rebuked the Cardinals in such unmeasured language for the lives they led and the splendor of their households that they could scarcely contain their anger. He seemed indeed to have the unfortunate gift of offending everybody. Queen Joanna of Naples, who had even sent Otho of Brunswick, her own husband, to Rome to offer her congratulations to the Pope, was so indignant at the way in which he was received that she, who might have been Urban's most powerful friend, became his bitterest enemy. Catherine learned something of what was going on in Rome from Fra Raimondo. "Act with benevolence and a tranquil heart," she wrote to Urban, whom she had known at Avignon; "for the love of Jesus, restrain those too quick movements with which nature inspires you. God has given you a great heart; I beg of you to act so that it may become great supernaturally, and that full of zeal for virtue and the reform of Holy Church, you may also acquire a manly heart, founded in true humility." Unfortunately Urban did not take her advice. One by one the French Cardinals withdrew to Anagni, followed by many prelates and officials of the papal court. They began to circulate reports that Urban's election had not been lawful; they had been forced to make him Pope, they declared, on account of the threats of the Romans. Catherine wrote to two of them of whom she had hoped better things. "I hear," she says, "that discord has broken out between Christ on earth and his followers ... I solemnly entreat you by the Precious Blood that has redeemed you, do not separate from your Head ... Alas, what misery! All the rest seems but a straw, a mere shadow, compared to the danger of schism." The danger, alas, had become a reality. The Cardinals had written to Urban commanding him to lay down his usurped dignity and, on his refusal, had proclaimed Cardinal Robert of Geneva, the cruel and bloodthirsty leader of the papal troops in Italy, as Pope under the title of Clement VII. The French King and Joanna of Naples at once acknowledged him, while many of the other nations found it hard to decide whether Urban or Clement was the rightful Pope. Richard II of England remained faithful to Urban, while the King of Scotland, David II, always a firm ally of the French, decided for Clement. The news went near to breaking Catherine's heart. "I hear," she writes to Urban, "that those incarnate demons have elected an Anti-Christ, whom they have exalted against you, the Christ on earth, for I confess and deny not that you are the Vicar of Christ." The great schism that was to last for forty years, to the desolation of all Christendom, had begun. With a fearless hand Catherine tore away the veils behind which the baseness of the Cardinals had been concealed from the eyes of the world. "You have deserted the light," she writes to them, "and gone into darkness; the truth, and joined you to a lie . . . I know what moves you . . . your self-love, which can brook no correction. ... For before he began to bite you with words and wished to draw the thorns out of the sweet garden, you confessed and announced to us that Pope Urban VI was true Pope. ... This last fruit that you bear which brings forth death, shows what kind of trees you are and that your tree is planted in the earth of pride, which springs from the self-love that robs you of the light of reason." Urban's position was a most difficult one. Left alone in Rome, deserted by all the Cardinals save one who remained only to die, he had created others to fill the vacant places, but he was surrounded by enemies. The castle of St. Angelo was in the hands of French captains who refused to give it up; the ships of Clement lay in the Tiber, while Joanna of Naples was gathering troops to march on Rome. Fra Raimondo of Capua, standing loyally by Urban, doubtless spoke often to him of Catherine and her efforts in his behalf. The Pope, remembering how at Avignon he had been struck by her wisdom and virtue, bade Fra Raimondo write bidding her in the name of holy obedience to come to Rome without delay. Once more therefore she left Siena and, with the usual little band of companions, made her way to the Eternal City, which she was never more to leave. Stefano Maconi remained behind at Siena, and it is from his correspondence with the family that we know much that happened during the stirring days that followed. The Pope received Catherine in a public audience immediately after her arrival and asked her to address the new Cardinals. She spoke to them in burning words of their duty to Christ and His Vicar, exhorting them to have confidence and faith, to do God's work and fear nothing. "This little woman puts us all to shame by her courage," said Urban when she had finished. "What need the Vicar of Christ fear, although the whole world stand against him? Is not Christ more powerful than the world? And He can never abandon His Church." She tried to impress on the Pope that he must seek to conquer his enemies by patience and charity. Though wholly in sympathy with his courage and zeal for reform, she could not fail to regret the violent temper that went so far to spoil all he undertook. But Urban was not an easy man to guide, and Catherine with gentle tact hit on a plan to make her advice acceptable. It was about Christmas time, and with her own hands, skilled in all housewifely labors, she prepared for the Pope a little present of oranges preserved in sugar and gilded. A letter accompanied the gift, in which, after expressing her great grief for the sorrows that were weighing so heavily on his heart, she writes: "That fruit (of suffering) seems bitter when first we taste it, but when the soul is resolved to suffer until death for Jesus Crucified, it becomes truly sweet." "So it is with the soul that loves virtue," she continues. "The beginnings are bitter ... but the waters of grace will draw out the bitterness ... and it is filled with the strength of perseverance while it is preserved in the honey of patience mingled with humility. Then when the fruit is finished and prepared, it is gilded outside with the gold of an ardent charity ... (which) appears in the patience with which the soul serves its neighbor, bearing him with great tenderness and steeping us in that sweet bitterness which we cannot but feel when we see God offended and souls perishing." The much-needed lesson could scarcely have been more delicately given. If anyone could have tamed the rough and violent Pontiff it would have been Catherine, and in her presence he seems to have been gentler than was his wont. She desired that he should surround himself with true and devoted servants of God, and it was at her suggestion that he wrote summoning to Rome several of her disciples in Siena, among them the Prior of Gorgona and the hermits of the wood of Lecceto. To her great astonishment, not to say disgust, some of them refused to leave their peaceful retreat to plunge into the turmoil of Rome. Catherine wrote to them in vigorous remonstrance: "If you would do any good, it will not do for you to stand still and to say, 'I shall lose my peace ...' Follow the call of God and of His Vicar ... quit your solitude and run to the field of battle." A second letter followed the first, which seemed to have failed in its effect. "This is the time for all true servants of God to show their fidelity and for us to see the difference between those who love God for Himself and those who only love Him for their own consolation ... It seems from the letter which Fr. William has sent me that neither he nor you intend to come. Fr. Andrea of Lucca and Fr. Paulinus have not acted so; they are old and infirm, but they set out at once." Since the days of her correspondence with the Queen of Naples on the subject of the Crusade, Catherine had followed the career of that most amazing woman with grief and many prayers. Joanna was now devoting herself heart and soul to the cause of the anti-Pope, and when Urban suggested to Catherine that she should go in company with St. Catherine of Sweden, at that time a nun in Rome, to try to win her over to the cause of the Church, she caught eagerly at the idea. Fra Raimondo was sent to talk the matter over with St. Catherine of Sweden. She was a daughter of the great St. Bridget and had known Joanna well of old, too well to be able to hold out any hopes of success. Fra Raimondo, who believed the Queen of Naples to be capable of any crime, feared to trust two defenseless women to her mercy and persuaded the Pope to give up the project. Catherine was greatly disappointed. She had hoped to win Joanna for Christ, and Fra Raimondo's prudence did not commend itself to her at all. "If Agnes and Margaret and so many other holy virgins had made all these reasonings," she said, "they would never have won the Martyr's crown." Perhaps the only man who could now have checked the schism was Charles V of France. The Cardinals who had caused it were Frenchmen, and their chief aim was the return of the popes to Avignon. They had urged on the King the advantages of this arrangement to himself, but he was still hesitating and not yet entirely committed to Clement's cause. Urban believed that if a trustworthy ambassador could be found who would undertake to set the true facts of the case before him, he might yet be gained. No one could be fitter for such a task, the Pope told himself, than Fra Raimondo, who had been in Rome at the time of the election and whose wisdom was equal to his holiness. In spite of her grief at the thought of losing him so soon again, Catherine was the first to urge him to go. Before he left Rome they had one last talk together. "Now, go where God calls you," she said when it was ended. "I think that in this life we shall never again speak together as we have done just now." It was perhaps because she knew the truth of her words that Catherine went with Fra Raimondo down to the Tiber, where the boat lay in readiness that was to take him on his journey. As it pushed out from the shore, she knelt and, weeping, made the Sign of the Cross over the beloved friend and father whom she was never to see in this life again. It was a difficult and dangerous mission, and her heart longed to share the peril. She dispatched a letter to meet the travelers at Pisa. "We must declare the truth," she says bravely, "and not keep silence out of fear, but be ready generously to give our life for Holy Church." To Catherine, Rome was above all things the city of the Church Triumphant. The noble army of Martyrs overshadowed it with their presence; the very ways she trod were hallowed by their footsteps and washed by their blood. To her the Colosseum was ever thronged with an invisible cloud of witnesses, men and women, aye, and children too, who had counted the world and all that was in it as loss that they might win Christ. Torn by the teeth of beasts or hacked in pieces by the weapons of the Roman soldiers, they had passed through the bitter anguish of the moment to the joy which is eternal-----from hope to vision. A beautiful story is told of St. Gregory the Great, how that when ambassadors of the Emperor Mauritius came to Rome asking for relics of the Martyrs, he bade one who was standing by take them to the Colosseum and give them a handful of sand from the arena. This was not what they had expected, and they complained to the Pope-----who, taking the sand in his hand pressed it gently, and lo! drops of fresh blood oozed through his fingers. "The sand of the Colosseum," he said reverently, "is soaked with the blood of the Martyrs." |

E-MAIL

E-MAIL

HOME--------------THE PASSION---------------SAINTS

www.catholictradition.org/Passion/siena8.htm