OF THE PASSION:

+++++++ Saint Catherine of Siena +++++++

| St.

Catherine of Siena: Biography Adapted by Catholic Tradition from SAINT CATHERINE OF SIENA by Mother Frances A. Forbes, a nun of the Society of the Scared Heart in Scotland who was a convert and highly regarded by Cardinal Merry de Val, a close friend of Pope St. Pius X. Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur, 1913. Currently published by TAN BOOKS. Chapter 5 IN GOD'S VINEYARD  N

the year 1374 the plague broke out in Siena. This terrible disease,

known in England as the Black Death, had made its first appearance in

Europe the year after Catherine's birth and swept over the whole of

Italy, causing frightful mortality. Men and women were suddenly

attacked while speaking to each other in the streets and died before

they could reach their homes. The death carts went from door to door

gathering up the dead, who were buried in great trenches outside the

town. The richer citizens hastened to the country to escape the

infection, but in many cases the disease followed them. The inmates of

the plague-stricken houses fled in terror, leaving the sick to die

untended. Bands of thieves, breaking into the rooms where the dead and

the dying lay, carried off all the rich garments and jewels that they

could lay hands on and sold their plunder in neighboring cities and

provinces, thus spreading the infection far and wide. N

the year 1374 the plague broke out in Siena. This terrible disease,

known in England as the Black Death, had made its first appearance in

Europe the year after Catherine's birth and swept over the whole of

Italy, causing frightful mortality. Men and women were suddenly

attacked while speaking to each other in the streets and died before

they could reach their homes. The death carts went from door to door

gathering up the dead, who were buried in great trenches outside the

town. The richer citizens hastened to the country to escape the

infection, but in many cases the disease followed them. The inmates of

the plague-stricken houses fled in terror, leaving the sick to die

untended. Bands of thieves, breaking into the rooms where the dead and

the dying lay, carried off all the rich garments and jewels that they

could lay hands on and sold their plunder in neighboring cities and

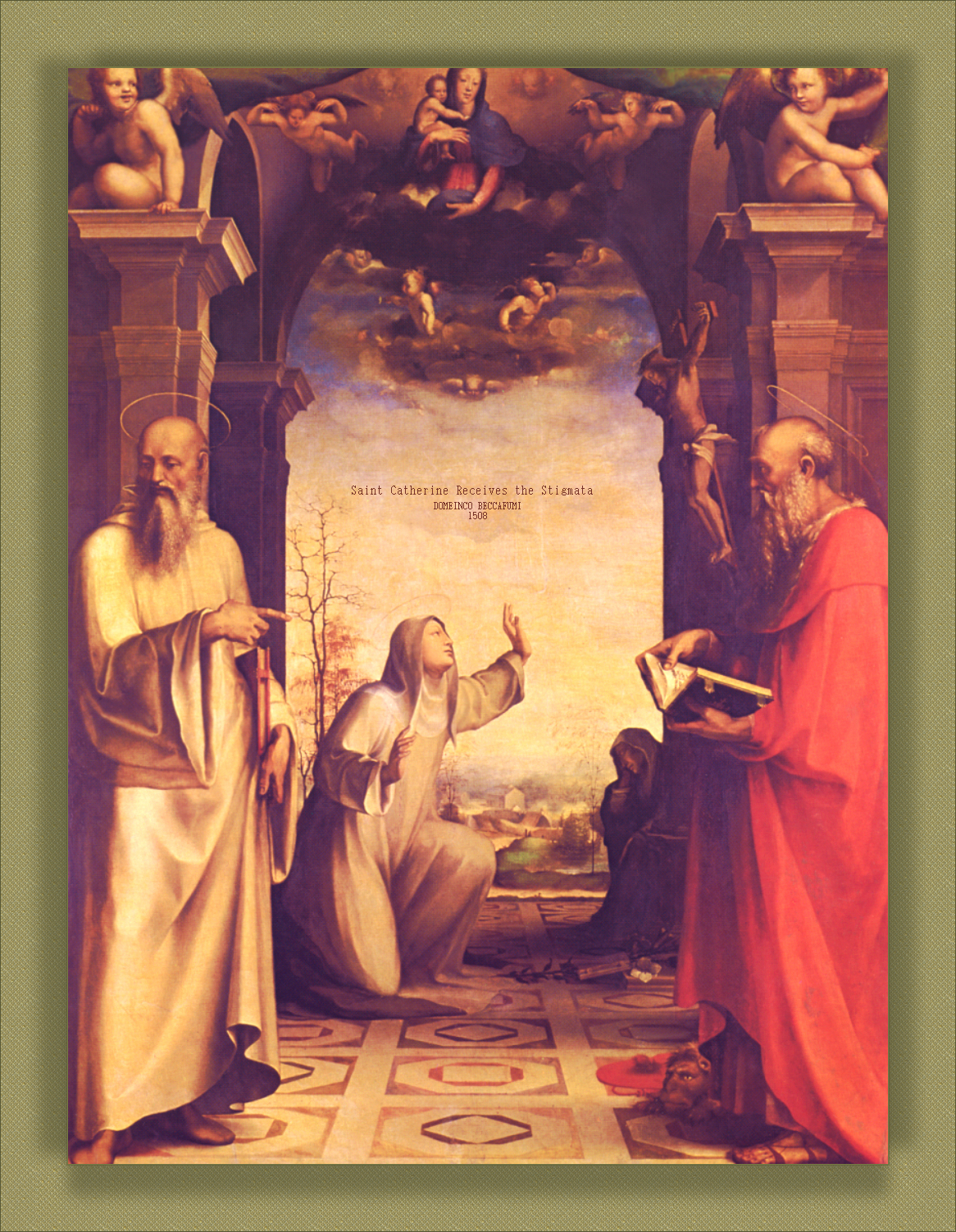

provinces, thus spreading the infection far and wide. Two of Catherine's brothers, her sister Lisa and several of the little grandchildren that Lapa was bringing up in her own house took the infection and died. Catherine tended them all and prepared the bodies for burial with her own hands. She wept over the little nephews and nieces that God had taken in the flower of their innocence, saying, to comfort her sad heart, "These, at least, I shall not lose." Then, with a little band of devoted companions-----Alessia, Cecca and the rest-----she went forth into the most infected parts of the city, going from house to house, succoring the living and burying the dead. In the places where the pestilence was raging most hotly these brave women would meet with another devoted little army-----Fra Raimondo and his friars, who had vowed to lay down their lives, if need be, for their people. Day and night they labored in the hospitals and infected houses, carrying the succors of religion to the sick and the dying. Many of these noble workers lost their lives. The rector of the great hospital of la Scala was stricken down at his post. Those who were carrying the dead to burial more than once fell lifeless and were buried in the still open grave. Messer Matteo, the rector of the Misericordia, while watching by a plague-stricken patient, was attacked himself by the terrible symptoms and sent for Fra Raimondo to make his last Confession. But Catherine, who knew the virtue of Messer Matteo and loved him much, hastened to the hospital. "Rise up at once, Messer Matteo!" she cried, as she entered the room where the sick man lay, "this is not the time to be lying in bed"; and at her words the sickness left him, and he who had been at the point of death rose up hale and strong and went back to his work in the hospital. Another friend of Catherine's, the old hermit Fra Santi, also contracted the disease and was cured by her prayers. Even Fra Raimondo did not escape. Feeling himself attacked by the plague as he was hastening through the city, he dragged himself with difficulty to Catherine's house, only to hear that she was absent. They sent for her in great haste. Laying her hand on the brow of the sick man, who was in great suffering, she knelt down beside him and fell into an ecstasy. As she prayed, the good friar felt the life returning to his aching limbs; and Catherine, coming to herself again, prepared food for him and bade him sleep. When he awoke he was perfectly well. "Go now," she said, "and work for the salvation of souls, and give thanks to Almighty God, who has preserved your life." Famine and disorders of all kinds followed in the footsteps of the pestilence. During the time of scarcity Catherine multiplied bread to feed the poor many times by her prayers, as several of her contemporaries bear witness. But the time of her great mission was drawing nigh. The country was in a sad condition. "Where is peace, where is liberty, where is tranquillity in Italy?" wrote a poet of the time. The Italian cities were either ruled by tyrants or, if republics such as Florence and Siena, were torn by internal quarrels and continually at war with their neighbors. Companies of foreign soldiers, ready to sell their swords to anyone who would pay them to fight, wandered through the country plundering and laying waste the land, unless bought off by the trembling citizens with large sums of money. Since the papacy of Clement V, the Popes had been at Avignon; and Italy, bereaved of her rightful protector, bewailed her desolation. The greatest writers of the time express the feeling of sorrow that prevailed. Dante, in the year 1314, had written a letter to the Cardinals at Avignon demanding the return of the Popes to Rome. "You, the chiefs of the Church Militant," he writes, "have neglected to guide the chariot of the Bride of the Crucified One . . . you, who have been the authors of this confusion, must go forth manfully with one heart and one soul into the fray in defense of the Bride of Christ whose seat is in Rome, of Italy, in short of the whole band of pilgrims on earth." To Rome the establishment of the Popes in Avignon was disastrous. The city was left to anarchy and misery, and many of its beautiful churches and buildings were falling into ruins. In 1370, three years before the outbreak of the plague in Italy, Gregory XI had succeeded Urban V on the papal throne. Gentle, scholarly and well-meaning, he was sickly in health and weak and irresolute in character. He was a Frenchman, and his love for his country and his own people scarcely seemed to point to a return to Rome. Catherine, true patriot and lover of the Church as she was, deeply deplored the state of affairs in Italy and with prayers and tears besought her Divine Spouse to put an end to the evils that were harassing the country. Then God made it known to her that she, a poor weak daughter of the people, was to act as His instrument-----not in her own power, but in lowliness of spirit, in utter trust of Him, a true reformer of the Bride of Christ. To her, the maiden image of the Italian people, it was to be given to reconcile the Pope with Italy and to bring him back to Rome. Catherine's was indeed the spirit of the true reformer-----regeneration, not destruction, was her dream. To her the Pope, whether Gregory or Urban, was the representative of God-----"Sweet Christ on earth," as she loved to call him. Clear of vision and strong in faith, she could look past the faults and weaknesses of human nature and see the thing signified behind the imperfect earthly form. She could denounce with unflinching honesty the corruptions of the time, but the Church of God was to her always the Mystical Body of Christ, the Bride of the Crucified, outside of which was neither light nor peace. She was already in correspondence with the Pope, urging him to remedy the existing evils, to be ready to give his life for Christ's flock and to act manfully, appointing only worthy men to rule the Church-----above all, to return to Rome. Her stirring appeal to all that was noblest and best in Gregory's nature, her gentle deference, the tender affection with which she wrote, now as a daughter to a beloved father, now as a mother to her son, would not fail in its effect. The fame of Catherine's holiness and the wisdom which brought men of all ranks, politicians as well as churchmen, to seek her counsel, had already reached the ears of the Pope. He sent word to Siena that everything possible was to be done to help her in her work for souls, and he even dispatched one of his vicars to Siena to take her his apostolic benediction and to ask her prayers. It was about this time that Catherine received an invitation from the ruler of the republic of Pisa to visit that city, and she set out accompanied by her regular companions and several Dominican friars, Fra Raimondo among the number. The Pisans received her as a messenger from God; her very presence seemed to draw men from sin to sanctity. So great was the reverence shown to her that some people were scandalized and others alarmed, lest she might be tempted to vainglory. One good man even took upon himself in all sincerity to warn her not to seek earthly praise or desire it. Catherine answered that she was deeply grateful for his care for her welfare and that she also often feared her own frailty and the deceits of the wicked one: "But I put my trust in the goodness of God," she continued, "and mistrust myself, for I know that on myself I cannot rely. I cling to the Holy Cross of Christ Crucified, and thereto I would be fastened." This desire was to be indeed fulfilled in a strange and supernatural way. Close to the house where Catherine lodged in Pisa was the little Church of Sancta Cristina, where she often went to pray and which was to be associated ever afterwards with one of the most wonderful events in her spiritual life. On Laetare Sunday, as she was rapt in ecstasy after Holy Communion, Fra Raimondo and the others who were present saw her rise suddenly and stretch out both her arms, her face shining with an unearthly light. After a few moments she fell to the ground in a swoon. Alessia and Cecca, who were close behind her, caught her in their arms and carried her back to her room in an unconscious condition. Later on Catherine told Fra Raimondo what had happened. She had seen, she said, the Crucified Lord coming down to her in a great light, while from His most Sacred Wounds five blood-red rays came down upon her feet and hands and heart, piercing them through and through. Though Catherine in her humility prayed that the sacred stigmata that she had thus received might be invisible during her life, after her death the marks of the Sacred Wounds were clearly visible on her body and were seen by several witnesses. Pope Gregory in the early days of his pontificate had thought of a plan to put an end to the continual fighting between state and state in Italy. This was to unite all the princes and rulers of Christendom in a Crusade against the infidels. This project he had confided to Catherine, to whom strangely enough the same idea had occurred and who determined to use all her influence to bring it about. In this way the Free Companies of foreign soldiers could be gotten rid of, their love of fighting could be used for a good object and the country delivered from one of its worst evils. "Raise the Gonfalon of the most Holy Cross," she wrote to the Pope, "for with the fragrance of the Cross you shall win peace." She herself, at Pisa, was doing all she could to stir up enthusiasm for the holy war, both by word of mouth and by her correspondence. Among the sovereigns and rulers whom she addressed was Joanna, the beautiful and wicked Queen of Naples, urging her in burning words to repent of her sins and to amend her life. "For Love's sake," she writes, "lift up the standard of the most Holy Cross in your heart ... in all that is possible show yourself a faithful daughter of sweet and holy Church." To several of the commanders of the Free Companies she also wrote-----among others, to the famous English freelance Sir John Hawkwood: "With desire to see you a true knight and son of Jesus Christ. Now my soul desires that you should change your way of life and take the pay and the Cross of Christ Crucified, you and all your followers and companions, so that you may be Christ's Company ... and thus you shall show that you are a true and manly knight." The letter touched the vein of chivalry that was latent in the famous "soldier of fortune," wild and lawless though he was, and that he and his captains took a solemn oath on the Blessed Sacrament "and signed it with their hands and sealed it with their seal" to join the Crusade if it were started, and that Sir John even made a vow to join henceforward only in lawful warfare. Joanna of Naples too was touched by Catherine's appeal to her better nature and promised her assistance. But the project so nobly urged was never realized. During the dark days that followed, the Pope had other affairs to attend to. The hour for the Crusade was past. |

E-MAIL

E-MAIL

HOME--------------THE PASSION---------------SAINTS

www.catholictradition.org/Passion/siena5.htm