Gallery , Section One

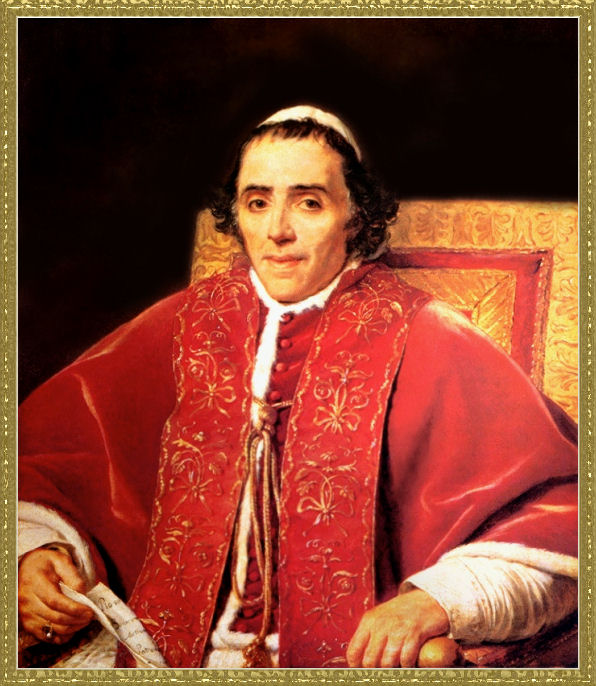

Pope Pius VII

JACQUES LOUIS DAVID

1748-1822

Mar. 21, 1800 to Aug. 20, 1823

VIEW ANOTHER IMAGE BY SIR THOMAS LAWRENCE: 1769-1830

PIUS VII 1800-1823

Barnabo Chiaramonti, born 1742

This Pontiff was known for his humility despite the great indignities heaped upon him as a prisoner of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The conclave which was to elect the successor of Pius VI met at Venice in the Benedictine monastery of S. Giorgio under the protection of the Austrian government on 30 November, 1799. Thirty-four of the forty-six cardinals were present, the secretary of the conclave being Msgr. Consalvi.

The long debate which filled the next three and a half months reflected both the disturbed political situation in France and Italy and the acute divisions in the Curia. There thus followed a deadlock which was finally ended on 14 March by the election of the Bishop of Imola, Cardinal Barnabo Chiaramonti. The new pope was enthroned in the monastic church of S. Giorgio on 21 March when Chiaramonti was crowned as Pius VII. After a long and trying journey by sea to Pesaro, the pope reached Rome on 3 July. In August he made Consalvi a cardinal and made him acting Secretary of State.

Barnabo Chiaramonti was born of a noble family of the Romagna at Cesena in 1742. At the age of sixteen he entered the Benedictine order in the neighboring monastery of S. Maria del Monte. After some years spent teaching theology and canon law at Parma and Rome he was made Bishop of Tivoli in 1782, and three years later cardinal and Bishop of Imola. As Bishop of Imola, Chiaramonti had sought a sincere understanding with the French after the Treaty of Tolentino and the establishment of the Cisalpine Republic in 1797. He was prepared to co-operate loyally with any form of civil government which would respect the freedom of the Church. The election of Chiaramonti as pope and the assumption of power by Napoleon Bonaparte seemed to promise the possibility of a new understanding between the Church and the Revolution.

By the defeat of the Austrians at Marengo in July, 1800 Bonaparte made himself master of northern Italy. He was by this time convinced that peace with the Church in France and an understanding with the papacy were essential for the restoration of order. The advantages to Napoleon of such an understanding were evident: the support of the Church would eliminate the legitimist opposition and provide a firm prop to his own authority. The text of a proposed concordat was approved in principle by Pius VII, and after several months of negotiation was signed in Paris in September 1801. By its terms Napoleon recognized that Catholicism was the religion of the majority of French people, and guaranteed freedom of public worship. The pope agreed to a complete reorganization of the Church in France. The concordat seemed a fair compromise, but when the text was published in Paris at Easter 1802 it was found that, of his own initiative, Napoleon had added a series of decrees, the "Organic Articles," which severely limited its scope. All bulls, briefs and rescripts from Rome were to be subject to the placet of the government. No papal legate or nuncio might exercise his functions without permission. The professors of theology in the newly established seminaries were to include the Gallican articles of 1682 in the syllabus of studies. Against all this the pope protested, but without effect.

On 4 May, the Tribunate proclaimed Napoleon as Emperor of France, and almost at once came the request for the pope to crown the new emperor. It was a request which could not be refused, but Pius VII used the opportunity to try and secure some modification of the Organic Articles. On 2 November the pope left Rome for Paris. He was treated with scant respect by the emperor; at the most solemn moment of the coronation ceremony, on 2 December, after the words Coronet te Deus, Napoleon himself placed the crown on his own head. He had, in fact, informed the pope beforehand that he intended to crown himself and Pius VII, having no choice in the matter, had reluctantly agreed to this novel procedure. It was a great insult to papal dignity, but in spite of such affronts, or perhaps in part because of them, Pius was greeted with the greatest enthusiasm by the people on whom he made an extraordinary impression. Indeed it was from this contact between Pius VII and the people of France that there developed that passionate devotion to the person of the Holy Father which was to be so characteristic of the nineteenth century.

In May 1805 Napoleon was crowned at Milan as King of Italy. The Code civil, which permitted divorce, was thus introduced into the country. Once again the pope could do little more than protest. In October the French occupied Ancona, and Pius VII protested at this fresh infringement of his sovereignty, and threatened to break off diplomatic relations. Early in 1806 Napoleon occupied Naples after marching his troops through the Papal States. It was by this time clear that the whole of Italy, including the pope's territories, was to be absorbed into the Empire. Napoleon now delivered an ultimatum: either the pope would join the confederation of his allies or he would be deprived of his temporal sovereignty. Pius VII rejected the offer of a treaty which would have destroyed his neutrality. In June 1809 General Miollis occupied Rome and formally announced that the city and the Papal State were incorporated into the Empire. On 6 July Pius VII, accompanied by Cardinal Pacca, left Rome under close guard, a prisoner of the French. His exile from the city was to last for five years.

The pope was taken first to Grenoble, and the later stages of the journey were almost a triumphal progress: he was everywhere acclaimed. This was not what Napoleon wanted, and he ordered him to be taken back to Savona. The cardinals were now summoned to Paris, and for a time it seems that Napoleon toyed with the idea of establishing the papacy permanently in France.

Deprived of his freedom and the counsel of the cardinals, Pius VII became once more the simple monk and refused to perform his office as head of the Church, and in particular to invest any French bishop. For three years Napoleon attempted without success to break the pope's resistance. The situation in the Church in France became an increasing embarrassment to the emperor. In June 1811 he summoned a national council of cardinals and bishops in Notre Dame and tried to persuade them that, if the pope refused to do so after a delay of six months, any metropolitan might lawfully invest the bishops of his province. But the members of the council refused to act without the pope's approval. After months of pressure the pope at last gave a reluctant consent to the emperor's proposal, redrafting the resolution so as to empower the archbishops to act in his name, but excluding from this general permission the right to invest bishops whose sees lay within the Papal State. Napoleon refused to accept the decision with this limitation, and Pius VII was saved from the consequences of a concession which he already regretted.

In May 1812 Napoleon ordered the pope to be brought from Savona to Fontainebleau. But for Napoleon this was to be the year of decision. After the disastrous failure of the Russian campaign he made one final effort to negotiate a new concordat. Before any agreement could be made the defeat of Leipzig marked the beginning of the end.

In January 1814 he ordered Pius to be returned to Italy, and in March the pope entered Rome. A month later Napoleon abdicated.

On recovering liberty of action, one of the pope's first measures was to decree the restoration of the Society of Jesus throughout the world. The Jesuits had, in fact, been able to ensure continuity through the protection of the two non-Catholic monarchs-----Frederick the Great of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia-----in whose dominions they were undisturbed.

The pope had won the admiration of the world by his heroic resistance to the emperor but already the latent conflict between the aspirations of the Italian people to self-government and the traditional form of the temporal sovereignty of the pope was becoming apparent when Pius VII died on 20 August, 1823 after a reign of twenty-three years.

All graphic accessories on this page copyrighted by Catholic Tradition.

Contact

Us-

Contact

Us-

TRADITION-----------------GALLERIES----------------------THE PAPACY

www.catholictradition.org/Papacy/papal-gallery3.htm